When we began our ongoing investigation here, Christa, who’s way more organized than I, suggested we do a Summer Camp to get our thoughts together. I figured it’d never happen. I was a lousy Girl Scout and dropped out early to join the kids who smoked cigarettes behind the junior high. When I found out she was serious, I was excited.

On our first day, I trundled my “girls” (Helen/Elaine and Taffeta Sash) over to Christa’s studio. She brought out “Isadora” or “Izzy”, a hand-crafted 25-30” skeletal Day of the Dead figure in black lace, a gift from her sister. I had never seen it, though I did know of its namesake, an ancestor of Christa’s who’d inspired many of her writings.

Christa told me of her long, imaginative history with dolls. She told me that when she was a child, she had a friend who would come over to her house with her own dolls and together they would create fabulous narratives.

If a doll’s function is to initiate us girls into the world of womanhood with our mothers modeling the role, they should have made an “Angry Barbie” for people like me. I have no doubt that my mother loved her kids fiercely, but she never wanted marriage or a domestic life for herself and felt trapped. Her mother, who had grown up poor in and around Houston (they spent some time as farm workers and lived in a tent on what now is I-45 South), graduated from high school at fourteen and immediately went to work at a local factory. She did a bang-up job of instilling in my mother a terror of poverty and black people and a love for conformity and appearances–and for seeing other women as “the competition”. She also loathed fat people, and my mother inherited her father’s stocky Dutch genes. My mom’s hatred of men was only surpassed by her hatred of women, and she impressed on my sister and me that sexuality was something we would have to endure in a school of unavoidable hard knocks that included sexual harassment and rape. It seems odd that a woman who marched for women’s rights, who was indicted for murder for shuttling women to abortion clinics, and who framed signs in the kitchen that read, “INSANITY IS HEREDITARY YOU GET IT FROM YOUR KIDS” and “I HATE HOUSEWORK,” could feel so limited.

My mother always talked a lot, but never about anything important. It was as if she thought that silence and contemplative space were voids that could be filled with chatter. I found out after she died that she’d been molested by a family member, and when she complained about it to her mother, she was told to shut up about it. She took her revenge–endless babble in a crushing monotone– out on everyone but the responsible parties.

Christa’s accounts motivated me to take a personal doll-history inventory, which I had a difficult time doing. My friends and my younger sister happily pushed those plump, rubbery baby dolls around in a dolly stroller, but I remember being adamantly against them for some reason. I do remember having stuffed animals.

My first real memories of actual dolls take place in Morenci, Arizona, when I was six.

My father had taken a job as a research chemist at Phelps Dodge, where they engaged in strip mining. We lived on a street lined with identical one-story brick boxes with sand and pebbled front yards. Our neighbors to the right were a nice Mexican family, the Alvarezes. Mrs. Alvarez taught my mother how to cook with chilis and comino and could make flour tortillas so thin that you could see the kitchen light fixture through the thin, circles of dough as she stretched them out into large circles.

I immediately became friends with Dora, who was my age. She had dark eyes, long black hair, and a calm expression on her round, flat face. Her father had built a pink and white playhouse in their sand and pebble backyard, and one day she invited me to stoop down with her to enter it. There were lace curtains and a small table and chairs. On the table was a miniature china tea set with a delicate floral pattern on the edges. Dora placed her pale-skinned baby dolls on the chairs, pushed them up to the table, and pretended to pour tea. I just stared at the scene in wonder. I’d never witnessed anything like it in real life.

A couple of weeks later, Dora’s father and brothers went hunting. I was the first one up the next morning and walked outside to the porch. Finding a large canvas duffel, I opened it. It was filled with dead doves. I woke my parents (and probably half the neighborhood) with my screaming and crying. I was inconsolable, so my father hefted the bag over his shoulder and returned it to Mr. Alvarez.

I never spoke to Dora again, even though we took the same bus to school and were in the same class. I never objected to eating meat, so I’m sure I happily munched on my beef burritos or tacos that night without making any connection.

I must have had Barbie dolls back then, for my grandmother sent several Barbie outfits, hand-crocheted by her neighbor, which I turned around and sold to the girls down the street. I further infuriated my grandmother when she came to visit us and offered to buy me a new Barbie doll. I chose a “Julia”. I still remember my mother telling her to get over it as my grandmother muttered her objections in the car on the way home.

At some point, a “Tammy” doll was added to our (mine and my sister’s) collection. Created by the Ideal Toy Company in 1962 to rival Mattel’s Barbie, who’d debuted three years earlier to over 300,000 sales, Tammy was supposed to be the girl next door rather than the siren. She had more rounded, childlike features and a flatter chest. Her measurements were more like that of a real pre-teen to teenage girl.

In contrast, the inspiration for Barbie was the German Bild Lilli doll, a risqué gag gift for men based on a cartoon character featured in the West German newspaper Bild Zeitung.

Why is it not surprising that the entire world would opt for a gag sex doll over a healthy role model?

More importantly, why are both Tammy and Barbie looking to their left? Why do they not frankly address their viewers with an unapologetic stare?

We moved a few more times and wound up in the Chicago suburbs. My sister and I would sometimes hang out, listlessly addressing our motley doll crew, and Tammy was always the designated mother. On more than one occasion, Tammy found herself buried up to her wholesome little neck in the front yard of our duplex in Park Forest, Illinois.

Unsurprisingly, every encounter I had with dolls afterwards, especially as an adult, has been hostile or ironic, which pretty much went along with my idea of myself as female. I was never alone. Most of my friends had or have a lot of disdain for Barbie, and I wholly embraced Todd Haynes’ dark take on Karen Carpenter’s life story dramatized with Barbie dolls – so much so that I did a Barbie video of my own (spoiler alert: the housekeeper kills everyone at a baby shower) and a full-scale mock wedding in commemoration of my own real wedding.

I derived a certain amount of glee from these projects, but I ultimately found them unsatisfying. Too cynical, too derivative, too cheap a shot at a seriously dysfunctional upbringing. Though it’s an awful lot of fun to ridicule things like this, when you’re the subject it becomes tiring. I put them aside, just as depressed and dissatisfied with myself as I was before I started. Everything was funny, everything was true, but that never made me feel better.

My paintings and drawings, equally dark, are slightly better gauges of my own ongoing investigation into what it means to be middle class and female, but because the sources that inspired them (fashion magazines) are also two-dimensional, the accusatory stares or simply blank expressions have always resonated with me but they never quite felt like me.

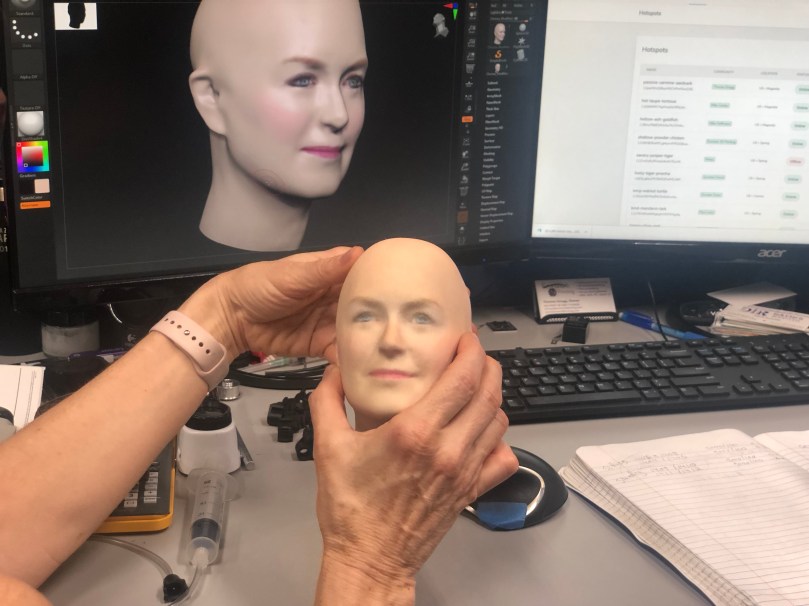

I guess that’s why this project has helped me finally get it–”it” being myself. When I look at this weird, powder-based 3D printout that was Frankensteined onto a plastic body, I feel something different, something necessary, for my psychic evolution. I now have a me that takes up space, demanding that I take care because of its fragility. It has provided me with a slightly better understanding of my own physicality. Of course, resignation and self-acceptance are also the ambiguous gifts of growing older, so perhaps the doll is less responsible for this newfound self-forgiveness than is the realization that, with so little time remaining on the clock, scathing criticism and self-abuse just seem pointless.

Ultimately, though, I must attribute the healing power of the doll to its own origins with my work in the Fashion Department at HCC. Although I wonder whether the majority of the students even know what art is for in a market-driven field, I realize that for the first time my projects which start on the page wind up as tangible objects. With every class I teach and take, I am reminded that the sketches and the ideas are a means to an end.

Last year I took a Theatrical Costume Design course with Nicolas ChampRoux. Having the doll allowed me to explore a lot of the material on a completely different level. Some of the course work helped me focus on narratives that I’d struggled to materialize for years, such as the “Mythical Creature” project, where I created the “Timberwerewolf”.

Another assignment forced me to delve deeply into the life of Jane Morris, which wasn’t easy, as history has focused more on her husband William Morris and her lover Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Apparently, the “thing” for cultured folks back then was to converse with the fabulous, self-educated Mrs. Morris–Henry James reported that no one came away disappointed.

These projects have changed the direction of my writing, too. Although I’ve been praised a few times for a number of frank autobiographical pieces I’ve written about my upbringing, I’ve felt guilty for exposing people and have harbored resentment towards my readers, and especially towards myself. I can’t help but think that had Tammy succeeded over Barbie, my mom would have been a little more kind to herself and other women. She would have had an avatar/image to identify with and create narratives with when she was far too young for ambiguity and irony–even when, at the age of 12, she looked and thought of herself as a fully formed adult . Her own single mother was probably so busy working her ass off to put food on the table and trying to have a life and hustle up that third husband, she wasn’t around to tell her what I’ve noticed that my most well-adjusted female friends know instinctively: that the person they really need to rely on for their senses of self-esteem is already looking back at them in the mirror.

Maybe recounting family dysfunction makes better literature than the story I’m presently illustrating. I get that feeling occasionally. But really? Fuck feelings. Those transitory, meaningless menaces have plagued me for far too long, and I’ve got a doll to play with.